- Details

- Hits: 4850

Story: The Grand Trunk Main Line - and how it got that way...

Reprinted with permission from September, 1972 edition of:

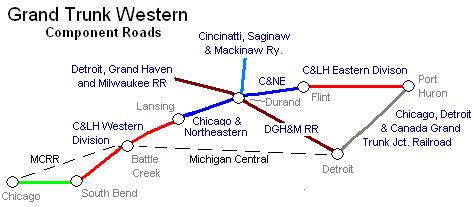

In 1859, the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada extended its rails to Sarnia, Ontario, and by means of a ferry to Port Huron and a lease of the Chicago, Detroit and Canada Grand Trunk Junction Railroad between Port Huron and Detroit, achieved a connection with the Michigan Central Railroad. Thus through freight and passenger service was maintained.

The Grand Trunk always seemed more than happy with this route to Chicago, but when the Chicago & lake Huron Railroad completed a through line from Port Huron to Valparaiso, Indiana early in 1877, officials at GT's home office in Montreal decided to play safe and began sending some Chicago business over the C&LH via the Great Eastern Fast Freight Line. The C&LH interchanged at Valparaiso with the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago (later the Pennsylvania) to reach Chicago.

The Grand Trunk always seemed more than happy with this route to Chicago, but when the Chicago & lake Huron Railroad completed a through line from Port Huron to Valparaiso, Indiana early in 1877, officials at GT's home office in Montreal decided to play safe and began sending some Chicago business over the C&LH via the Great Eastern Fast Freight Line. The C&LH interchanged at Valparaiso with the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago (later the Pennsylvania) to reach Chicago.

The C&LH was a financially embarrassed railroad which actually consisted of two separate divisions - an Eastern Division extending from Port Huron to Flint, and a Western Division between Lansing and Valparaiso. In 1876, using C&LH money and manpower, the gap between the two divisions was closed and by January 1, 1877, the C&LH had a continuous route from Port Huron to Valparaiso. However, since the C&LH was in bankruptcy, the Flint-Lansing segment was built under the name of the Chicago & Northeastern.

James Turner of Lansing was President of the C&NE and he was not to sell stock or bonds to anybody without due notice to the harried stockholders of the C&LH. Early in 1878, however, when William L. Bancroft was displaced as receiver of the C&LH and replaced by Charles W. Peck, superintendent of the railroad, Turner secretly sold $1,200,000 in bonds to William K. Vanderbilt of the New York Central, giving Vanderbilt control of the line.

Vanderbilt didn't take any action to curb Grand Trunk traffic until late June of 1878. On June 24th, he acquired control of the Michigan Central and then on June 27 the C&NE segment of the Chicago & Lake Huron was blockaded at Flint. Such high freight rates were established that through freight service was impossible. That GT freight was the target was obvious since through passenger service was continued, although C&NE crews had to handle the trains between Flint and Lansing.

Vanderbilt thus had the Grand Trunk at his mercy and this was a position he had long sought. Because of its less direct route from Portland, Maine to Chicago, the GT has always been permitted to charge lower rates for freight. And to add to Vanderbilt's animosity toward the GT, the other eastern trunk lines (the Pennsylvania, the Baltimore & Ohio, the New York, Lake Erie & Western) tended to side with the GT in rather violent rate wars that raged at infrequent intervals.

In June of 1878 for example, the GT's freight charges were five cents a hundred-weight lower and through passenger fares were two dollars less. And since 1873, when the GT changed its tracks to standard gauge, it had shown the mode rapid traffic growth of any of the eastern trunk lines.

In June of 1878 for example, the GT's freight charges were five cents a hundred-weight lower and through passenger fares were two dollars less. And since 1873, when the GT changed its tracks to standard gauge, it had shown the mode rapid traffic growth of any of the eastern trunk lines.

When the GT's shareholders met in London, England on October 29, 1878, Sir Henry Tyler, President of the GT, told them that all the GT wanted was "fair and durable arrangements" with Vanderbilt for interchange of traffic with the Michigan Central and the avoidance of competition with other sections of the vast Vanderbilt rail system.

Less than two months later, angry stockholders of the Chicago & Lake Huron were in Montreal to confer with Grand Trunk officials. They were angry because Vanderbilt, supremely confident that he could pick up the C&LH whenever he wanted it, hadn't treated them too well when they talked with him in New York.

It didn't become public knowledge for about six months but on December 24, 1878, the Grand Trunk achieved an agreement with the C&LH bondholders that set the stage for the acquisition of the present Grand Trunk Western trackage.

Bolstered by this agreement and spurred into action by a decline of $457,000 in revenues during the last half of 1878 because of traffic losses at Port Huron and Detroit, Sir Henry faced the shareholders again on April 29, and publicly declared the GT was going to fight for an independent route to Chicago.

He visited Detroit in May, 1879 and started wild rumors as to the route the GT would take. Rumors continued when he visited Chicago. Sir Henry sailed from New York on June 20. At noon the next day in Detroit, the first piece in the jigsaw puzzle of the GT's new route fell into place: the Eastern Division of the C&LH was purchased at auction for $300,000.

Charles Peck was named general manager pro tem and took charge of the Port Huron-Flint segment on June 22. While the agreement with the C&LH bondholders gave encouragement about the acquisition of both divisions of the bankrupt line, there was still the problem of the C&NE between Flint and Lansing.

On July 30, Peck advertised for bids to build a railroad from Flint to Lansing which wouldn't quite parallel the C&NE since it would swing a bit to the north and pass through Corunna and Owosso, tapping coal fields east of Corunna to supply fuel for the railroad's locomotives.

The rest of the puzzle kept falling into place: the Western division of the C&LH was acquired at auction for $300,000 on August 26, the section from Lansing to the Indiana state line. Peck also became pro tem general manager of that bit of railroad.

By this time, Vanderbilt was beginning to know he was up against a tough fighter in battling Sir Henry Tyler. Right after bids had been asked to solve the Flint-Lansing problem, a Vanderbilt attorney approached the GT's lawyers in Michigan and made an offer to sell Vanderbilt's interest in the Chicago & Northeastern for $600,000. The GT countered with $450,000 and a compromise at $540,000 was reached, and an agreement was completed on September 3rd.

Now the Grand Trunk had a route from Port Huron to the Indiana border. The C&LH segment from the border to Valparaiso was bought on November 2, 1878 for $200,000. Construction work was under way on a railroad from Valparaiso to Thornton, Illinois, to connect with a line of road into Chicago acquired earlier by the Grand Trunk.

The new railroad was completed early in February and the first Grand Trunk train ran out of Chicago on Saturday night, February 7, 1880. There was extensive track work going on because the Port Huron Daily Times reported the arrival of the first freight on Monday, February 9 at 7:30 p.m.

The new road was an immediate success. Shippers in Chicago welcomed the Grand Trunk because the road was not a part of the Joint Executive Committee set up in 1878 with Albert Find as chairman in an effort to bring some sense of order into the rates charged by the eastern and western trunk lines.

However, relations with the Michigan Central were maintained by the Grand Trunk and there were two sets of officials soliciting traffic for the Grand Trunk: one set seeking to lure shippers into using the Chicago and Grand Trunk (the name for the new route to Chicago) and the other seeking freight to be routed via the Michigan Central to Detroit and then onto Grand Trunk tracks.

Sir Henry's twice-yearly reports to the stockholders were sure to contain a reference each time to the troubles arising out of the efforts to do business with the Michigan Central. Even as late as October 25, 1883, he said that if the Michigan Central had not been controlled by Vanderbilt, "we never should have had a Chicago and Grand Trunk because we always should have been satisfied to have worked with the Michigan Central as long as it was an independent line, working fairly and honestly with us." By about 1885, however, he seems to have become reconciled to doing all his business with the Chicago and Grand Trunk.

The present Grand Trunk Western trackage across the state all came under Montreal's control during the ten years that followed the entry into Chicago. On August 12, 1882, the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee (Successor to the Detroit & Milwaukee, one of Michigan's pioneer railroads) was acquired when the Grand Trunk took control of the Great Western Railway, a Canadian line with considerable trackage in Ontario and which had an outlet into Detroit through a line from London to Windsor. The Great Western had long been active in exchanging traffic with the D&M and had actually acquired control of the Detroit-Grand Haven line in 1877.

In his history of the Canadian National Railways, G. R. Stevens relates how two more bits of present-day GTW lines were acquired: "...Tyler took over one line in Michigan that he did not particularly want and was given another railway that his shareholders were loath to accept.

"The first was the Toledo, Saginaw and Muskegon Railway from Ashley, 20 miles northwest of Owosso, to Muskegon on Lake Michigan, a distance of 96 miles. (This is the present Greenville Sub of the GTW, but the rails now end at Greenville.) It had been incorporated in 1886 and built almost entirely with borrowed funds in the next two years.

"When it opened it had no money, no traffic and no prospects. It made connections with the Grand Trunk at Owosso by means of running rights over the tracks of the Toledo, Ann Arbor and North Michigan Railway; it ran through quite promising countryside but it was almost, if not quite, parallel to the Grand Trunk line to Grand Haven and there were grave doubts as to whether it would ever pull its weight. On the other hand, some competitor might take it over and so damage still further the prospects of the never-prosperous Detroit-Grand Haven division. Tyler decided that it was worth the gamble and on May 10, 1888 the Grand Trunk obtained possession by guaranteeing the interest on its funded debt of $1,560,000 in 5% bonds.

"The gift that the British shareholders scrutinized with such suspicion lay in the Saginaw Valley. There, a number of industrialists, feeling the need of a railway, had set to and built one. They raised capital by what they described as the "hello method"; when they needed cash they did a whip-around by telephone. In 1890 the Cincinnati, Saginaw & Mackinaw, 54 miles long, was opened for traffic between Durand, Saginaw and Bay City. (This is the present Saginaw Subdivision of the GTW).

"A few weeks later, one of the proprietors of the CS&M turned up in London. He offered the railway to Sir Henry for its bonded debt. He stated that he and his friends had had dealings with various Michigan railroads and they had come to regard the Grand Trunk as the best of the lot. They had been genuinely impressed by the workman-like manner in which the St. Clair Tunnel had been built.

"Sir Henry was gratified by such appreciation and he sent engineers to examine the railway. They reported that if anything the owners had been too modest; the line was excellently built and well worth the liability involved which was the service of $1,680,000 in 5% bonds. A small percent of the operating revenue would be sufficient to cover such charges. But after misgivings, the line was taken into the fold.

NOTE: Much of this article appeared first in the Durand Express, May 18, 1961.

Bibliography

The following sources are utilized in this website. [SOURCE-YEAR-MMDD-PG]:

- [AAB| = All Aboard!, by Willis Dunbar, Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids ©1969.

- [AAN] = Alpena Argus newspaper.

- [AARQJ] = American Association of Railroads Quiz Jr. pamphlet. © 1956

- [AATHA] = Ann Arbor Railroad Technical and Historical Association newsletter "The Double A"

- [AB] = Information provided at Michigan History Conference from Andrew Bailey, Port Huron, MI